I was working with a personal training client who was having trouble packing his shoulder in the one-arm kettlebell swing, particularly in the hike pass position. He had no problems with this in his two-hand swing, it only happened when he switched to the one-arm swing. So, I used the RKC towel pull drill with him and voila! It taught him the feeling of properly loading in the hike position and it improved his shoulder packing when he went back to swings.

This client trains with me once a week to learn proper kettlebell technique, and the rest of the time he trains on his own at home. How could he duplicate this drill on his own when he didn’t have a training partner or qualified instructor to train with him at home? We needed a solution so that he could practice the drill prior to each set of one-arm swings, at least until he was able to groove the pattern in his swings.

The deadlift drag is a wonderful exercise and I use it quite often. In this drill, you set up as if to swing, but instead, you drag the kettlebell on the floor very slowly, keeping yourself in the hike position and loaded up through the posterior chain the whole time. However, I sometimes find that the deadlift drag doesn’t have the same carry-over into the swing itself. Not every drill will work for every person to correct the pattern they need to correct. In this case I wanted my client to be able to really load up in the same way we do with the towel pull drill since it really worked to help his one-arm swing. I wanted him to have his arm connected to his body as if the kettlebell were behind him like it is in the hike position of the swing.

I came up with a similar drill using a resistance band. I used a band that was about 1/2” wide, that provides about 15-30 lbs of resistance. Keep in mind that you’re using a double thickness of the band when you set it up as I have in the video below. The loading in this drill happens from the front as you are pulling the band behind you, rather than loading from the back in the towel pull drill. But, the drill still worked really well for my client. He got his shoulder packed in the hike position and felt the loading and support that comes from the shoulder position in the in the swing.

We did one set like you’ll see in the video below and it had the same positive effect on his one-arm swing technique as when we did the towel pull drill together at the gym. The best part is that he can now do the resistance band drill when he trains by himself at home. I prescribed for him to do about five pulls of the band, followed by one 10-second static hold before every set of one-arm swings.

https://youtu.be/9Ac8T1bpdpo

I did experiment with this same idea, and we turned around to try and load up from the back, in order to really try and emulate the towel pull. I personally didn’t like this as much as pulling from the front, because I felt like the resistance of the band wanted to pull me backwards and without a partner to brace against in the pull, I didn’t feel like I was in control of the movement as much. I also didn’t feel like I could engage the lats and the hips in the same way or to the same extent.

I invite you to try this drill both ways and let me know what you think in the comments section below!

Here’s a quick workout you can do using this resistance band drill, the deadlift drag, and the all-important single rep swing. Hopefully the combination will really help your one-arm swings.

- 5 1-arm deadlift drags, left side

- 5 single rep swings, left side

- 5 band pulls, left side with :10 hold on last rep

- 10 1-arm swings, left side

- Repeat on the right

Repeat for 5-10 sets, resting as needed between sets

****

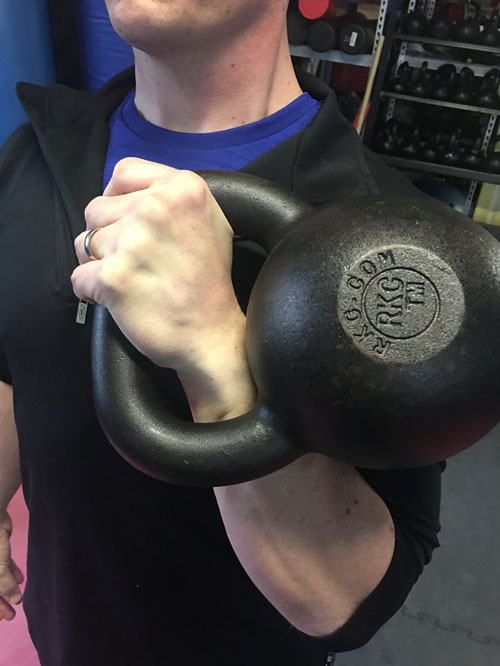

RKC Team Leader Shari Wagner, RKC-II, PCC, CK-FMS owns Iron Clad Fitness in Denver, Colorado. She can be contacted through her website at IronCladFit.com, email: info@ironcladfit.com or by phone 720-900-4766. Follow her on Facebook: facebook.com/IronCladFitness and Twitter: twitter.com/IronCladFitness.