When entering a room where RKC kettlebell training is in progress, one quickly notices the characteristic way people breathe while performing the exercises. Although this “grunting” may sound unfamiliar and disconcerting at first, breathing in sharply through the nose and breathing out slowly while gritting the teeth should become a part of everyone’s training routine.

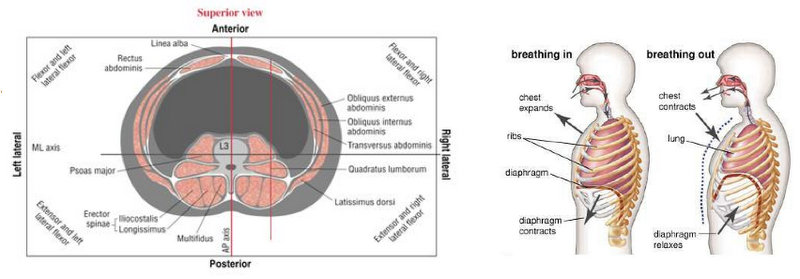

In order to understand why we use the “biomechanical breathing” method for improved performance and safety, we first need to talk about the anatomy of the trunk and core. Today, most researchers agree that the lumbar region is an area that relies heavily on stability and where excessive range of motion should be avoided (Battie et al, 1990; Biering-Sorenson, 1984; Cuoto, 1995; Saal & Saal, 1989; McGill, 2010). In the original sense, the widely-used term “core stability” describes “the ability of the lumbopelvic hip complex to prevent buckling and to return to equilibrium after perturbation” (Wilson et al., 2005). In other words, core stability is the ability to produce and maintain a neutral lumbar spine (Gottlob, 2001). According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, keeping a neutral spine is recommended when lifting something heavy off the ground or being under load…

Several muscles, such as the latissimus dorsi, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, multifidii, and obliques—but also the glutes and adductors contribute to the stability of the core (Filey, 2007). More importantly, most of these muscles are connected via the thoracolumbar fascia, thereby forming a natural weightlifting belt around the lumbar spine. In conjunction with the diaphragm and the muscles of the pelvic floor, they help to maintain or build core stability by forming a shell around the lumbar region. Contracting the core and hip muscles leads to muscular stiffness and therefore the flexibility of the shell decreases and becomes more rigid. Filling the rigid shell with air by sharply inhaling through the nose will increase the so-called intra-abdominal pressure, leading to greater compression of the spine and consequently higher intervertebral stiffness (increased lumbar spine stability).

A sharp inhalation has the advantage of automatically contracting the core muscles, which does not happen during slow breathing. The same effect is observed when exhaling while gritting one’s teeth—sufficient intra-abdominal pressure is maintained because more air will remain in the respiratory pathways while air flow is constricted. Continuous breathing allows continuous spine stability and is therefore preferable to the “valsalva maneuver”, when performing a task for more than one repetition. In support of this theory, Stuart McGill (2007) reported that using this breathing technique—known as “kime” in martial arts—when performing swings lead to a significantly greater contraction of the obliques. Thus, safety and performance can be enhanced by just breathing the right way.

***

Felix Sempf M.A. Sportscience, RKC, FMS, PM trains and instructs at the FIZ in Göttingen, Germany. He can be contacted by email at: felix.sempf@sport.uni-goettingen.de and his website: http://www.kettlebellperformance.de